MS Drug Does More Than Treat Symptoms, It Rewires the Immune System

In a major breakthrough, Yale University researchers have discovered that a commonly used multiple sclerosis (MS) drug does more than alleviate symptoms, it rewires the immune system itself, potentially transforming long-term treatment strategies.

The study, published in Nature Immunology, focused on dimethyl fumarate (DMF), a widely prescribed oral therapy for relapsing MS. While DMF is known to reduce inflammation and relapse rates, scientists have now shown it causes lasting changes in immune cell behavior, offering new insight into how the drug may alter the course of disease.

“What we found is that DMF doesn’t just put out the fire,” said senior author Dr. David Hafler, professor of neurology and immunobiology at Yale. “It rebuilds the firehouse.”

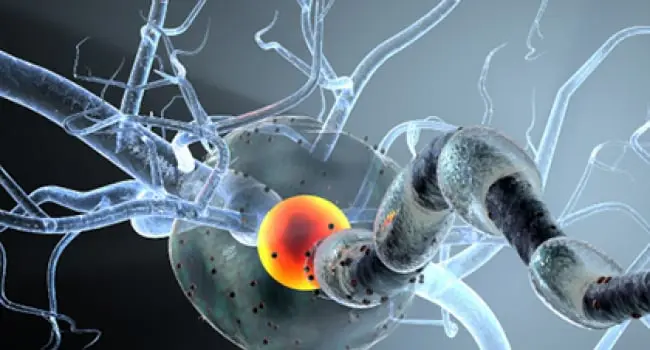

MS is an autoimmune disorder where the immune system mistakenly attacks the brain and spinal cord, causing a range of neurological symptoms. DMF works by dampening this overactive response, but until now, the mechanisms were poorly understood.

Using single-cell RNA sequencing, the team analyzed blood samples from MS patients before and after starting DMF. The results showed a significant shift in immune cell populations, including reductions in pro-inflammatory T cells and increases in regulatory T cells that help prevent autoimmune damage.

Even more striking, these changes persisted months after treatment began, suggesting the immune system was not just suppressed but fundamentally reshaped.

“This opens up the possibility that MS therapies could go beyond symptom control,” said Hafler. “We might be talking about retraining the immune system, which is the holy grail for autoimmune diseases.”

The findings could also help identify biomarkers to predict who responds best to DMF, and who might benefit from other immunomodulatory drugs.

As the landscape of MS treatment evolves, this study pushes the field closer to precision medicine, where therapies don’t just mute disease activity, but reshape biology at its roots.